- Se incorporó

- 28 Octubre 2004

- Mensajes

- 8.729

Hola,

Acá un bonito articulo de un gringo que el año 2002 viajó 22.000 kilometros en un Subaru Legacy Turbo del 91:

http://motyka.kinja.com/that-one-time-i-drove-to-the-bottom-of-argentina-1493997357

Un testimonio a la confiabilidad que tienen estos antiguos Subaru .. ignoro si los actuales tendrán la misma resistencia

Para mi, lo mas increíble fue el leer que la famosa carretera "Panamericana" está cortada entre Panamá y Colombia .. investigué un poco para ver si esto aun es así ... y efectivamente, aun hoy no es factible pasar en auto por tierra y esta uno obligado a hacer parte del trayecto por mar si o si.

Saludos,

Rudel

It was a warm August night in 2002 when I picked up my driving partner in Cambridge, MA. Plan was to spend as little time as possible driving through the U.S. so that we could leave the rest for crossing Central and South America all the way south.

I'll spare you the details of the few run-ins with traffic law enforcement in US or near loss of all travel documents in Houston, TX Kinkos parking lot where I was scanning and printing a copy of my car's license plates — when driving through Central America in a car with foreign license plates you want to have a laminated copy of your license plate attached to the car rather than the original - in case the original walks off in shadier part of town.

The drive through Mexico was mostly uneventful apart from one episode of money extortion from local authorities in Veracruz. Traffic cops simply stopped us for no reason and demanded my Passport. I already knew from reading up a little before the trip that giving up your Passport was a bad move and $40 was all it took to continue on our way south to Guatemalan border.

Guatemala is where things got more interesting. Roads were visibly worse than in Mexico (mind you, we were on the Pan-American highway). Our first encounter with a large pothole resulted in an immediate flat. We were in the middle of nowhere and getting the wheel swapped with a spare as quickly as possible felt like the right thing to do. The full size jack I packed along with few other essentials came in handy more than once throughout the trip.

Our fears were not unbased. When we pulled into a local gas station later that night and chatted with a local he warned us of not driving these roads at night. Two weeks prior he was robbed of his own car by a group of bad guys. They set up a road blockade with their pickup trucks and were robbing at gunpoint.

Having received that warning we took to driving during daytime only. Which was not without its own difficulties. At least we could see further ahead and had better chances of reacting in time.

Border crossings in Central America provided an experience of its own. It was often more time consuming than the driving part. The mid countries of Central America (El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica) can be driven across in matter of hours each but the wait on border and the amount of paperwork required would push the crossing itself into 6-7 hour ordeal. Part of the complication was obviously the requirement to get visa for the car on each border. Local kids that swarmed the car upon arrival would prove immensely helpful in the process of guiding us through the maze of various "border offices". It reminded me more of a local swap meet than a border between two countries.

A smooth, newly built highway greeted us in Honduras. Surprisingly, the worst roads were waiting for us in Costa Rica though. There, after paying a speeding ticket in cash on a stretch of curvy tarmac, we hit roads that really didn't have much in common with the word 'road'.

They often were impassable due to an array of obstacles - A bus that clearly should not have been there:

River crossing that popped up without any warning whatsoever.

Or a bridge you had to assemble yourself before use (something I later learned was just a gimmick for the uninitiated one once I noticed a local charging full speed across, clearly relying on the "faster you go, the less chance you have to fall through" rule).

Reaching Panama felt like scoring major achievement points. It's also where the Pan American truly becomes impassable. The hundred-mile stretch of jungle called Darien's Gapexists to this day between Panama and Colombia and serves as political / social / economic natural barrier between Central and South America. Only dedicated 4x4 equipment can cross it.

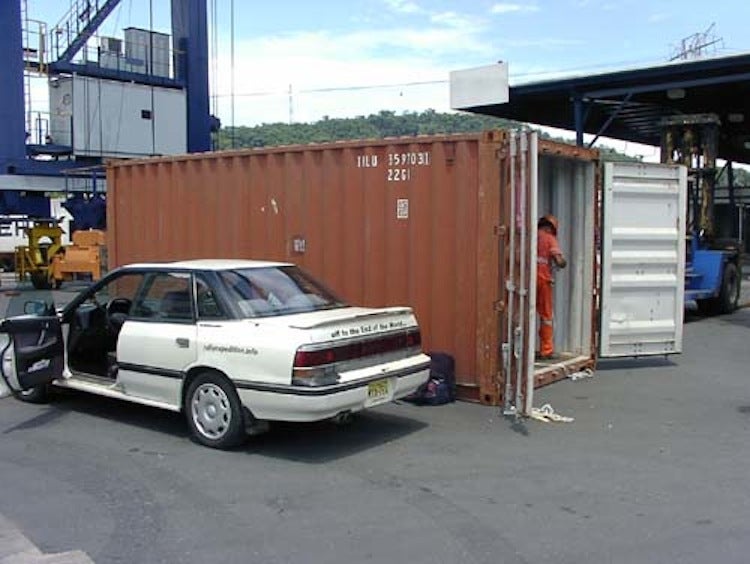

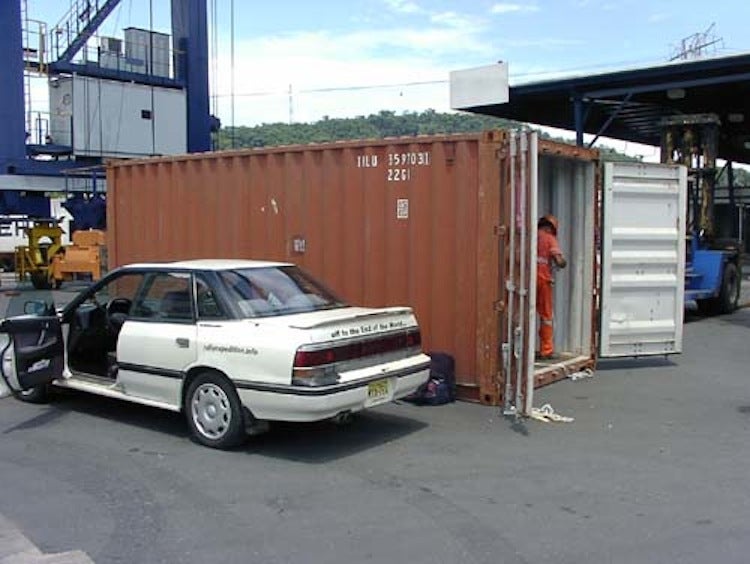

For us it meant loading the car onto a container ship in Panama City and picking it up at the destination port of Lima, Peru. I'll leave out the details of the required paperwork and the language barrier / logistical nightmare experienced when interacting with local shipping agencies and customs authorities.

South America greeted us with undoubtedly smoother ride. No traffic rules to be seen either but covering larger distances at a time was very much possible.

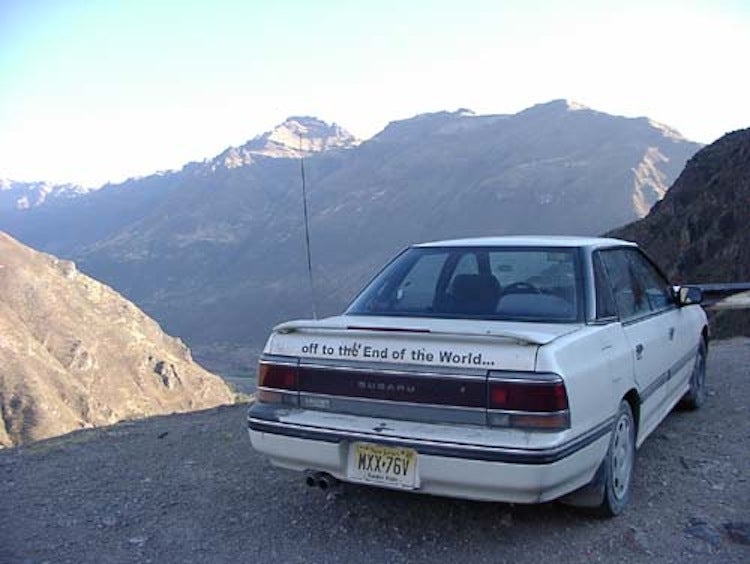

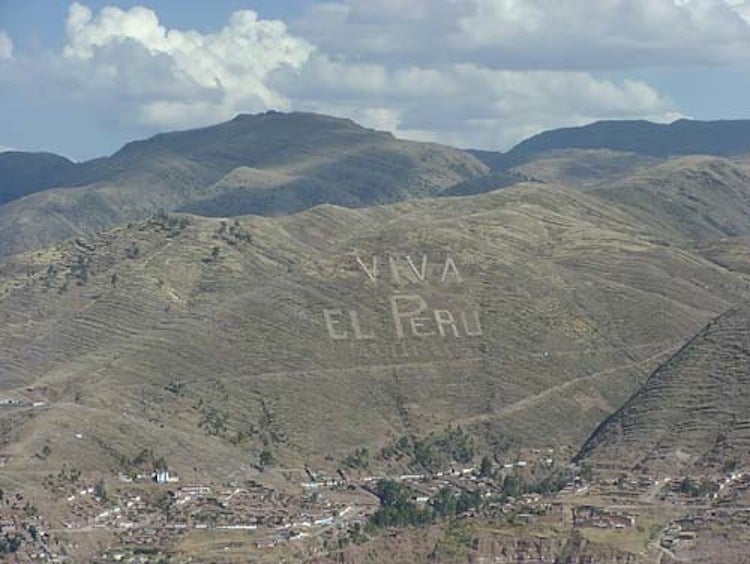

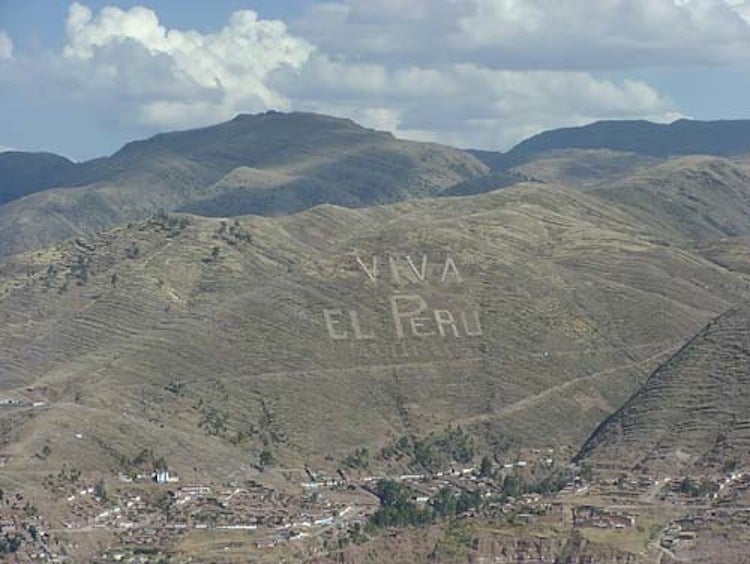

Improved road infrastructure made it also feasible to venture off a bit into amazing locations such as Machu Picchu. Driving through Andes proved to be unforgettable and extreme experience.

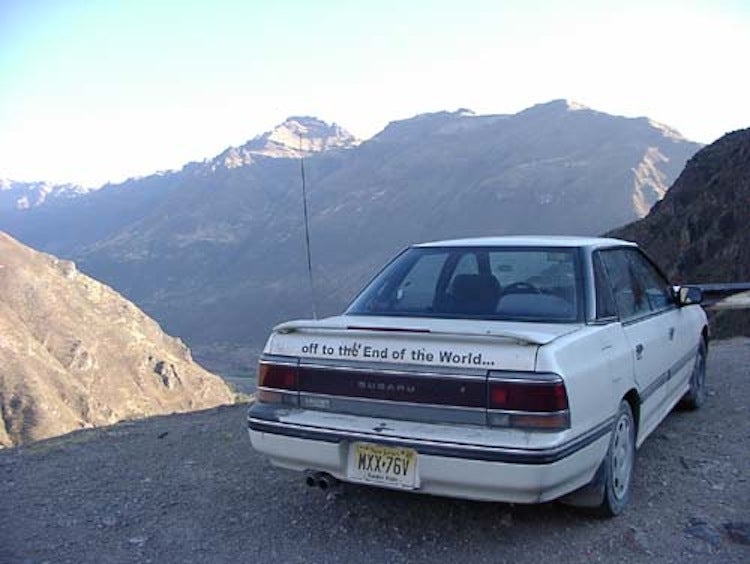

Coming back down from Machu Picchu and getting into a parked car that was still on New Jersey plates felt weird but also somewhat familiar and uniting — as if the world suddenly become that much smaller. Just like any other weekend mountain hike where you'd come down to your car parked after a day of hiking only this time it was half way down the globe.

Driving on smoother roads didn't come free of danger. Just because the road was well maintained it didn't mean it couldn't end abruptly at any given moment, in fact it did on numerous occasions without warning. Smaller potholes at speed still posed considerable risk.

Key to continuing this journey was to stay alert and always carry two full spare metal wheels. Metal rims have the tendency to bend rather than break which can then be fixed at the next road-side shop with no more than sledgehammer at the disposal. Aluminum wheels are stronger but will crack rather than bend and therefore become irreparable in field conditions. Also, by mounting stronger wheels damage can occur "higher up the chain" — suspension parts and drive train components, which then become even harder to repair. I did carry a few critical spare parts known to fail on this car (ignition coil, axle, alternator) but none of them proved needed. Here is damage to front wheel from hitting a bump on otherwise smooth highway.

Leaving Peru behind, Chile proved smooth sailing and occasional stops were only made for food and shelter.

Entry into Argentina got exciting again. Weather was markedly colder and the combination of rain and worn tires resulted in an off-road incident — spin into a ditch at a rather brisk pace on a particularly winding stretch of Patagonian two-lane blacktop.

Luckily it all ended with just three bent wheels which were fixed again without much problem in the next town — only getting there was a bit of a hassle as the car was crabbing heavily at 5 mph. I kid you not, the mechanic took to one of the wheels with a sledgehammer with the wheel still on the car. The good Samaritan that pulled us out with his pickup truck invited us into his house and offered a home cooked meal and hot tea. The warmth of Argentinian people seemed to contrast the windy and cold vast expanse of southern Argentina.

At the bottom of continental Argentina all that remained was to cross onto the island of Tierra Del Fuego, "land of fire", separated by one-hour ferry ride from the mainland. There it was back to business as usual, at this point also caring less about saving the car and pushing more on unpaved sections of the road.

Reaching the bottom of Tierra Del Fuego - Ushuaia - the most southern permanent settlement on Earth turned out to be pretty uneventful. Apart from spirited driving on the last two hundred miles of unpaved road it almost felt monotonous.

Also, at this point my brain and I were probably less aware of the smaller stuff and the car itself reached some kind of mechanical-failure equilibrium with few, less critical components failing long time ago (no odometer, distinct smell of gas, weak or no heat...) but all the major mechanical bits still worked fine — if not for the worrying sounds coming from the rear differential. The car just kept on going.

In the end, lack of time made the return trip in the car not possible. Next day in Ushuaia I booked a flight to NYC and with the registration plates and my tool box in hand I hopped on the plane back.

Acá un bonito articulo de un gringo que el año 2002 viajó 22.000 kilometros en un Subaru Legacy Turbo del 91:

http://motyka.kinja.com/that-one-time-i-drove-to-the-bottom-of-argentina-1493997357

Un testimonio a la confiabilidad que tienen estos antiguos Subaru .. ignoro si los actuales tendrán la misma resistencia

Para mi, lo mas increíble fue el leer que la famosa carretera "Panamericana" está cortada entre Panamá y Colombia .. investigué un poco para ver si esto aun es así ... y efectivamente, aun hoy no es factible pasar en auto por tierra y esta uno obligado a hacer parte del trayecto por mar si o si.

Saludos,

Rudel

It was a warm August night in 2002 when I picked up my driving partner in Cambridge, MA. Plan was to spend as little time as possible driving through the U.S. so that we could leave the rest for crossing Central and South America all the way south.

I'll spare you the details of the few run-ins with traffic law enforcement in US or near loss of all travel documents in Houston, TX Kinkos parking lot where I was scanning and printing a copy of my car's license plates — when driving through Central America in a car with foreign license plates you want to have a laminated copy of your license plate attached to the car rather than the original - in case the original walks off in shadier part of town.

The drive through Mexico was mostly uneventful apart from one episode of money extortion from local authorities in Veracruz. Traffic cops simply stopped us for no reason and demanded my Passport. I already knew from reading up a little before the trip that giving up your Passport was a bad move and $40 was all it took to continue on our way south to Guatemalan border.

Guatemala is where things got more interesting. Roads were visibly worse than in Mexico (mind you, we were on the Pan-American highway). Our first encounter with a large pothole resulted in an immediate flat. We were in the middle of nowhere and getting the wheel swapped with a spare as quickly as possible felt like the right thing to do. The full size jack I packed along with few other essentials came in handy more than once throughout the trip.

Our fears were not unbased. When we pulled into a local gas station later that night and chatted with a local he warned us of not driving these roads at night. Two weeks prior he was robbed of his own car by a group of bad guys. They set up a road blockade with their pickup trucks and were robbing at gunpoint.

Having received that warning we took to driving during daytime only. Which was not without its own difficulties. At least we could see further ahead and had better chances of reacting in time.

Border crossings in Central America provided an experience of its own. It was often more time consuming than the driving part. The mid countries of Central America (El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica) can be driven across in matter of hours each but the wait on border and the amount of paperwork required would push the crossing itself into 6-7 hour ordeal. Part of the complication was obviously the requirement to get visa for the car on each border. Local kids that swarmed the car upon arrival would prove immensely helpful in the process of guiding us through the maze of various "border offices". It reminded me more of a local swap meet than a border between two countries.

A smooth, newly built highway greeted us in Honduras. Surprisingly, the worst roads were waiting for us in Costa Rica though. There, after paying a speeding ticket in cash on a stretch of curvy tarmac, we hit roads that really didn't have much in common with the word 'road'.

They often were impassable due to an array of obstacles - A bus that clearly should not have been there:

River crossing that popped up without any warning whatsoever.

Or a bridge you had to assemble yourself before use (something I later learned was just a gimmick for the uninitiated one once I noticed a local charging full speed across, clearly relying on the "faster you go, the less chance you have to fall through" rule).

Reaching Panama felt like scoring major achievement points. It's also where the Pan American truly becomes impassable. The hundred-mile stretch of jungle called Darien's Gapexists to this day between Panama and Colombia and serves as political / social / economic natural barrier between Central and South America. Only dedicated 4x4 equipment can cross it.

For us it meant loading the car onto a container ship in Panama City and picking it up at the destination port of Lima, Peru. I'll leave out the details of the required paperwork and the language barrier / logistical nightmare experienced when interacting with local shipping agencies and customs authorities.

South America greeted us with undoubtedly smoother ride. No traffic rules to be seen either but covering larger distances at a time was very much possible.

Improved road infrastructure made it also feasible to venture off a bit into amazing locations such as Machu Picchu. Driving through Andes proved to be unforgettable and extreme experience.

Coming back down from Machu Picchu and getting into a parked car that was still on New Jersey plates felt weird but also somewhat familiar and uniting — as if the world suddenly become that much smaller. Just like any other weekend mountain hike where you'd come down to your car parked after a day of hiking only this time it was half way down the globe.

Driving on smoother roads didn't come free of danger. Just because the road was well maintained it didn't mean it couldn't end abruptly at any given moment, in fact it did on numerous occasions without warning. Smaller potholes at speed still posed considerable risk.

Key to continuing this journey was to stay alert and always carry two full spare metal wheels. Metal rims have the tendency to bend rather than break which can then be fixed at the next road-side shop with no more than sledgehammer at the disposal. Aluminum wheels are stronger but will crack rather than bend and therefore become irreparable in field conditions. Also, by mounting stronger wheels damage can occur "higher up the chain" — suspension parts and drive train components, which then become even harder to repair. I did carry a few critical spare parts known to fail on this car (ignition coil, axle, alternator) but none of them proved needed. Here is damage to front wheel from hitting a bump on otherwise smooth highway.

Leaving Peru behind, Chile proved smooth sailing and occasional stops were only made for food and shelter.

Entry into Argentina got exciting again. Weather was markedly colder and the combination of rain and worn tires resulted in an off-road incident — spin into a ditch at a rather brisk pace on a particularly winding stretch of Patagonian two-lane blacktop.

Luckily it all ended with just three bent wheels which were fixed again without much problem in the next town — only getting there was a bit of a hassle as the car was crabbing heavily at 5 mph. I kid you not, the mechanic took to one of the wheels with a sledgehammer with the wheel still on the car. The good Samaritan that pulled us out with his pickup truck invited us into his house and offered a home cooked meal and hot tea. The warmth of Argentinian people seemed to contrast the windy and cold vast expanse of southern Argentina.

At the bottom of continental Argentina all that remained was to cross onto the island of Tierra Del Fuego, "land of fire", separated by one-hour ferry ride from the mainland. There it was back to business as usual, at this point also caring less about saving the car and pushing more on unpaved sections of the road.

Reaching the bottom of Tierra Del Fuego - Ushuaia - the most southern permanent settlement on Earth turned out to be pretty uneventful. Apart from spirited driving on the last two hundred miles of unpaved road it almost felt monotonous.

Also, at this point my brain and I were probably less aware of the smaller stuff and the car itself reached some kind of mechanical-failure equilibrium with few, less critical components failing long time ago (no odometer, distinct smell of gas, weak or no heat...) but all the major mechanical bits still worked fine — if not for the worrying sounds coming from the rear differential. The car just kept on going.

In the end, lack of time made the return trip in the car not possible. Next day in Ushuaia I booked a flight to NYC and with the registration plates and my tool box in hand I hopped on the plane back.